Small Peek Into The Past

-

Forum Statistics

352.3k

Total Topics4.6m

Total Posts -

Member Statistics

125,479

Total Members2,078

Most OnlineNewest Member

avtoservis_fmsn

Joined -

Images

-

Albums

-

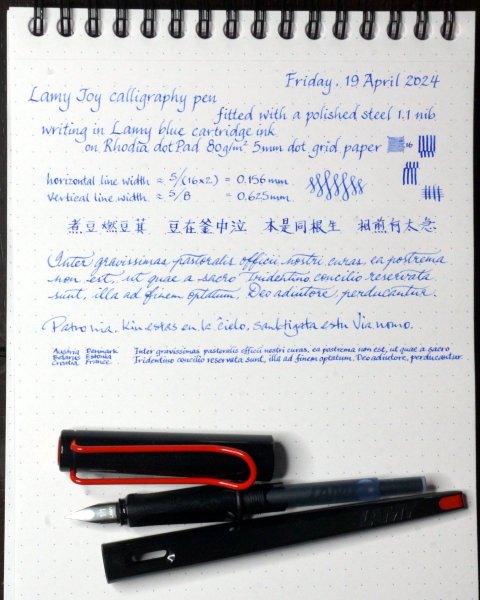

European pens

- By A Smug Dill,

- 12

- 32

-

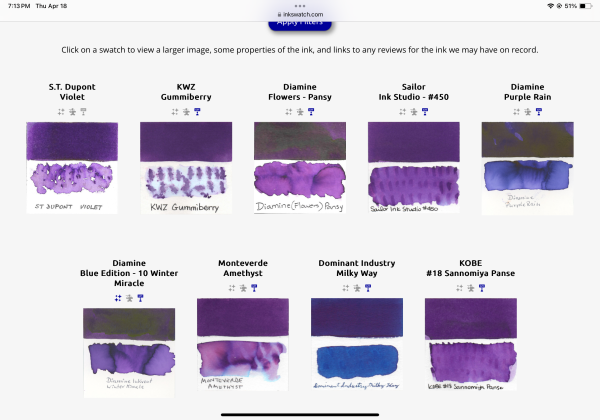

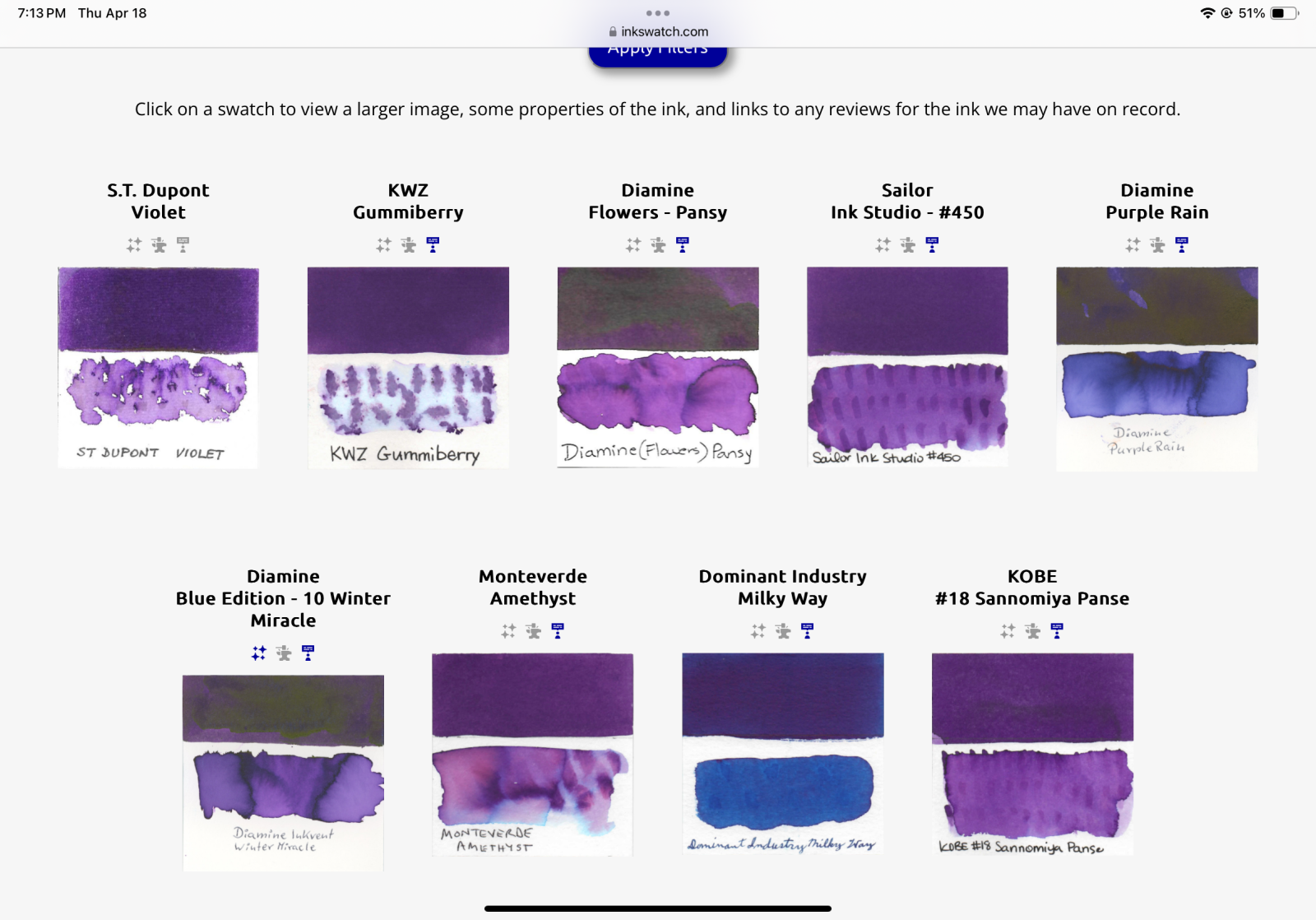

Ink

- By Penguincollector,

- 0

- 1

- 6

-

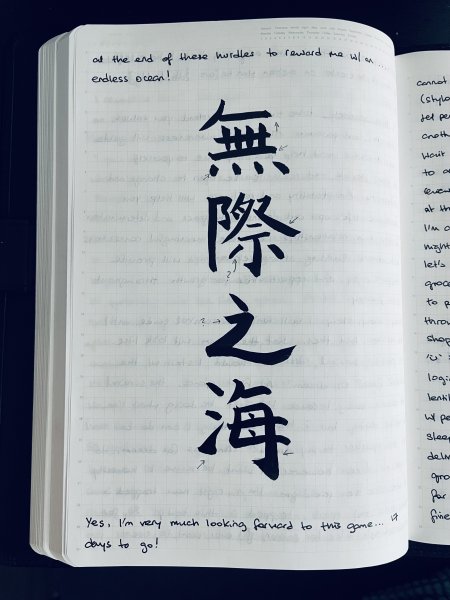

j1tters

- By 2ouvenir,

- 0

- 0

- 16

-

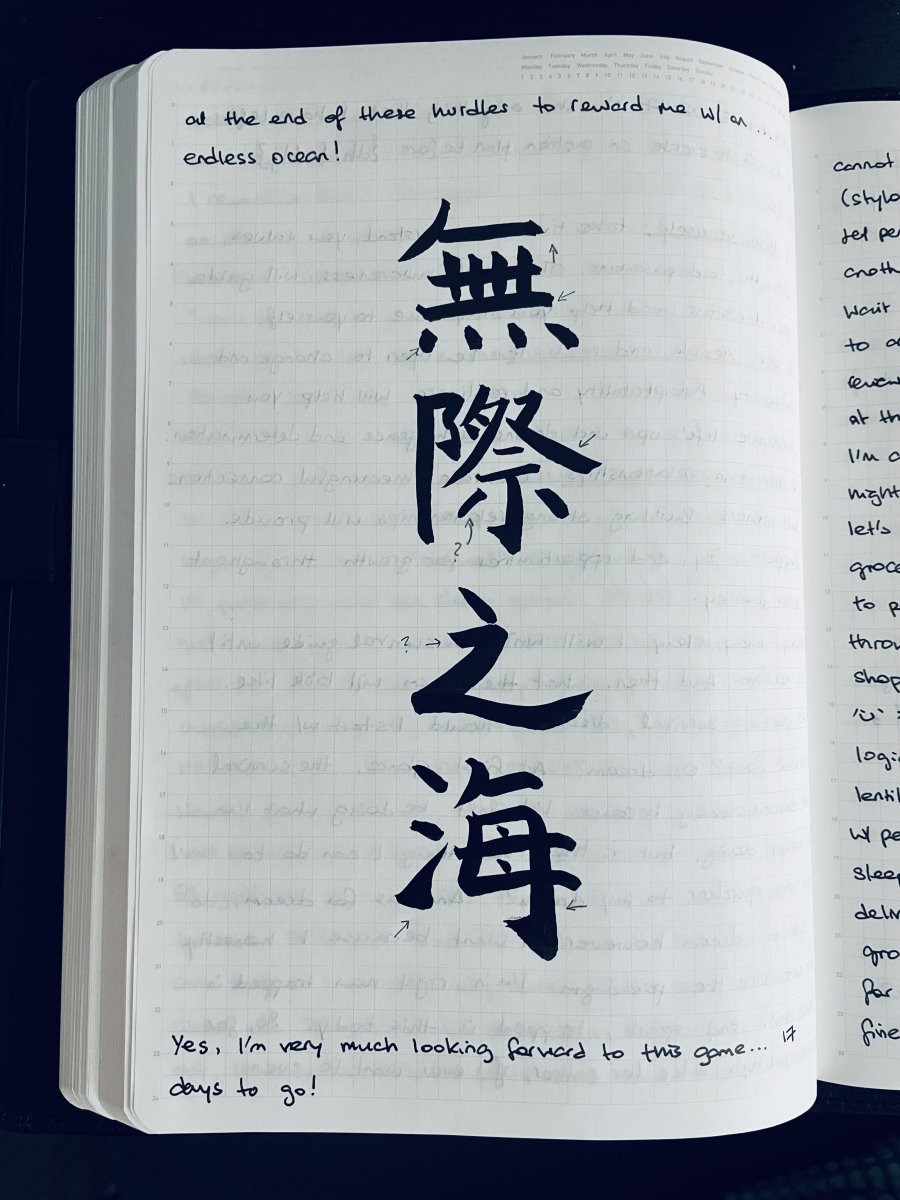

more

- By AmandaW,

- 3

- 3

- 65

-

Glamour Shots

- By Penguincollector,

- 0

- 0

- 1

-

.thumb.jpg.f07fa8de82f3c2bce9737ae64fbca314.jpg)

desaturated.thumb.gif.5cb70ef1e977aa313d11eea3616aba7d.gif)

Recommended Posts

Create an account or sign in to comment

You need to be a member in order to leave a comment

Create an account

Sign up for a new account in our community. It's easy!

Register a new accountSign in

Already have an account? Sign in here.

Sign In Now